2018-05-25

Rest In Peace, TotalBiscuit.

Rest In Peace,

John Peter “TotalBiscuit” Bain

July 8, 1984 - May 24, 2018

This is an early WIP focused on experimenting with ways to manage my blog posts before migrating my old blog to this website.

2018-05-25

Rest In Peace,

John Peter “TotalBiscuit” Bain

July 8, 1984 - May 24, 2018

2018-05-19

In my last post, I briefly discussed the impending closure of Funorb on the 7th of August this year, and that I started recording all my Arcanists gameplay in order to keep an archive of my final moments of fun with the game.

This highlights a problem in gaming where online games die without official support for playing them past server shutdown. We want to play the game, we bought copies of the game, and the code for the servers to make the game run exists, yet because someone decided it to no longer be a benefit to run them, that’s it. The game’s gone.

This can be particularly frustrating for the fans, and it certainly sucked when I heard that about Jagex’s Funorb, which hosts my childhood favourites Arcanists and Steel Sentinels, along with other great games like Armies of Gielinor and Void Hunters.

Even with the limitations my parents put on my gaming habits back during highschool and the fact that I only had a Funorb subscription for a few short months (since we didn’t have a credit card and I was paying through a friend), I racked up 1080 ranked games with Arcanists and 309 ranked games with Steel Sentinels, equating to 347 hours of ranked gameplay (assuming 15 minutes per game), and many more unranked games (particularly with Steel Sentinels). I absolutely loved Arcanists and Steel Sentinels back then, and I still believe they’re amazing and fun games that I’d love to return back to on occasion, even if it’s just to play with friends and have some casual fun.

Similarly, I was a huge fan of EA’s Battleforge back in the day for its unique and riotous-fun take on the real-time strategy formula, awesome theme, and its lovely and colourful art direction.

Battleforge shut down on the 31st of October, 2013, which was also the day of my highschool HSC Physics exam. Despite the importance of that exam, I still decided to make the most of Battleforge’s final hours, even sleeping at my computer desk with Battleforge open the night before the exam.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="90%" width="90%"}Thankfully, it’s not always doom and gloom. If a game is popular enough, people are smart enough to eventually figure something out.

Player-made private servers are a staple for MMORPGs such as World of Warcraft, Runescape, older titles such as Ultima Online, and dead titles such as Star Wars Galaxies.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="90%" width="90%"}Even for currently-supported MMORPGs such as World of Warcraft, private servers are still popular for allowing players to play older versions of these titles, particularly if these older versions are preferred over newer versions, or simply for the nostalgia. Private servers also naturally gave full control to the community, and even allowed adding of custom content to the games.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="90%" width="90%"}Moving away from MMORPGs, many other online games have also been successfully revived by players.

Official servers were axed in 2011 for Supreme Commander: Forged Alliance, though LAN play and a campaign were still available. The Forged Alliance Forever project was the community’s response to this, giving the game a multiplayer lobby and match-making (thus avoiding the need for VPNs) that continues to run to this day, and a community client with frequent patching for bug fixes and balance changes.

The Forged Alliance Forever client even goes well-beyond the game’s original functionality, adding additional features such as improved map and mod management, online map/mod/replay repositories, social features, a rating system, and co-op campaigns.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="90%" width="90%"}Allegiance is a shining example of what happens when a company supports its community’s efforts for revival. Allegiance’s online servers got the axe back in 2002, but succeeded well beyond its expiration date thanks to its small but loyal following.

LAN play was originally supported, which allowed the community to continue playing in a limited fashion. In 2004, Microsoft released the source code under a shared software license, smoothly allowing continued development by the community under the name FreeAllegiance and allowing the hosting of a community-driven online lobby. And just last year, Microsoft converted the software license to the open-source MIT license, allowing the game to be re-released onto Steam.

I discovered the game around 2005 through a free games magazine and despite being absolute terrible at it, I played the game for years until my family upgraded all the computers to Windows Vista. I stopped playing due to lack of support for Vista, though it improved eventually, allowing me to occasionally dive back in.

Despite the dated graphics and technology, Allegiance in my opinion stands the test of time for its uniqueness, community, and gameplay breadth and depth that few games are able to compare with.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="90%" width="90%"}On the other side of the spectrum, companies are also known to flex their legal rights against server emulators, with Asheron’s Call and it sequel Asheron’s Call 2 being merely two examples of emulator efforts falling to legal cease and desist orders.

Turning our sights back to Funorb and Battleforge, perhaps there’s still hope.

Hanging around the Funorb unofficial Discord, there are certainly talks of reverse-engineering the games and building server emulators, and people who seem to have looked through the code and the internal game logic. While I haven’t seen anything concrete yet, I’m quite hopeful that someone’s going to make a server emulator at some point. I might even take the challenge up myself if need be (it can be a great learning experience!).

Also, at the time of writing, a Battleforge server emulator seems a lot closer to being “ready”, with this recent announcement by the Skylords Reborn project on progress towards an open beta, and videos of the game working such as this video with early-alpha footage:

Really, it’s all just a matter of time.

There will always be a time when a games company no longer sees the continued support of an old game viable. The reason for this I think is fairly obvious: games companies are businesses, and legal complications may even prevent them from acting for the interests of the players.

Even if a company wanted to release server software, they’d need to spend time sanitizing it to remove anything unfit for distribution, and this could even prove impossible depending on the design of their systems. And even with the technical challenges sorted, unless a games company is doing it for PR, there’s no good reason for them to spend employee hours to solve both the technical and legal challenges that may exist.

There’s also the problem of avoiding cannibalizing its newer products, further disincentivizing any good will. As an example, consider a scenario where a company wants to release a new online-only arena shooter while also killing off support for an older online-only arena shooter. If the company released server programs for the old title, they’d consider it more likely that some people (no matter how small) who would’ve bought the newer title would instead continue playing the older title. It may not even matter how small the possibility is for the release of server programs to cannibalize. Releasing server code can potentially pull customers from any present and future titles.

Keeping assets as close as possible is also advantageous, giving a company more exclusive rights and control over the market. Relinquishing a great deal of control over a product and allowing public hosting means they lose the option of reusing it at a later date, perhaps to revive and subsequently monetize it, or to sell the assets off to another developer.

I’m sure there are plenty more points of discussion, especially since I haven’t even attempted to touch any legal problems that may arise (such as re-licensing). But the point still stands: companies gain nothing from giving communities control and can even suffer for it, so why should they bother?

Letting go of a well-loved videogame can be particularly painful. Oftentimes, we’ve invested so much of our lives on the particular game, spent so much time playing it, thinking of how we could get better at it, formed communities and friendships, and made plenty of fond memories. Even if you hardly play a particular game nowadays, losing the ability to play it can feel like losing a part of your life.

For games with no dependence on online services (such as retro console games and most single-player PC games), it’s not too bad to simply lose the disk, cartridge, and/or console. Someone probably ripped it and the game is probably playable on a console emulator. Or in the worst case, you’d likely still be able to find a second-hand copy of the game for sale somewhere, and an old console or a copy of Windows 95 to play it with. Everything is self-sufficient enough that it’s quite easy to go back to.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="70%" width="70%"}But for online games with complete dependence on online services, the loss of these services renders them completely unplayable on their own. The online server components are often highly complex yet kept secret by the company that hosted them, meaning a major technical effort is required by a group of skilled reverse-engineers in order to bring it back. Depending on the game, this can take years before an acceptable server emulator is developed (if at all). It’s been almost 5 years yet the Skylords Reborn project is only just moving towards an open-beta for its Battleforge server emulator. And even if the game gets a server emulator, its accuracy depends on how well people understand the game from the outside. (Exact precise accuracy may not matter, but it’s still worth noting.)

If the game is niche, unique, and actually good, its loss can be even more painful. If similar-enough games exist, then the loss of an original isn’t so bad. They won’t be the same, but they can be similar enough to still enjoy the same gameplay. However, this is certainly not the case for Arcanists, Steel Sentinels, Battleforge, and Allegiance. All of these are great games that offer unique gameplay elements and combinations unseen elsewhere.

(REMOVED IMAGE DUE TO COPYRIGHT)

{:height="90%" width="90%"}The uniqueness factor perhaps applies a bit less to Supreme Commander’s fairly bread-and-butter RTS gameplay (not to mention the fact that the campaign and LAN are still playable without servers anyway). However, I contend that Supreme Commander offers a well-crafted, timeless take on the genre that is difficult to replace, so it offers itself as an example, showing that you don’t need to be particularly niche to be sorely missed.

Two points must first be made:

Thankfully, the law could soon protect community-run online game revival efforts in the US, though the Entertainment Software Association opposes this, arguing that laws exempting officially abandoned games from DMCA takedowns can be seen as a form of competition against currently supported titles.

If the legal issues are solved, one might consider that it doesn’t matter too much to get companies to distribute their proprietary game server programs. It’s only a matter of time before someone builds an emulator, and “the problem of building a server emulator is someone else’s problem, not mine”. But what if we avoided the need to emulate from scratch anyway? Instead of thousands of developer hours merely getting something to work, all that effort could instead be fast-tracked with the release of source code or even merely the compiled server programs. Developer hours could instead be spent on improving on what already exists, or even working on completely new projects.

I won’t attempt to discuss the legal aspects of the problem of the release of proprietary game server code (I’m completely the wrong person to talk law), but assuming the legal problems are all sorted, we’d need companies to take an interest in consumer rights, and the technical challenges would need to be addressed. Unfortunately, these require businesses to act on good will, actively costing them man-hours that they technically don’t need to spend.

At the end of the day, the preservation of online videogames is not the end of the world. But the code exists, so why can’t we use it to play these damn videogames?

2018-05-13

Recently, Jagex announced the upcoming closure of their mini-games site, Funorb (see the announcement here). Funorb is a childhood favourite of mine, and I absolutely love Arcanists and Steel Sentinels, so it pains me to know that I may never be able to play these games again.

Thankfully, we’ve at least been given 3 months notice along with free paid membership, so I decided to take the opportunity to not only play the game, but record it and dump the videos on YouTube unedited along with full voice chat with my friend.

My original reason was of course for archival purposes. I wanted to record practically all matches I play, perhaps along with commentary, and upload everything mostly unedited. Eventually, I should end up with a big catalogue of videos that I can look through one day to maybe relive the game a bit, from my younger-self’s perspective. I’m making these videos mainly for myself, but I also want to put it out there on YouTube to maybe be discovered by others. If I end up with an audience, then cool, I guess.

Naturally, this prompted another idea:

What if I record all my other gameplay and put it on YouTube?

(Or well, maybe not all my gameplay, but the idea’s there.)

As already discussed, it could be interesting to archive everything, essentially building up a big time capsule of my gameplay. Technically speaking, this entire venture shouldn’t cost me much (although my PC is 6 years old at this point, so it might struggle to record later games). All it should cost is a bit of extra time to set up recording software, then to upload videos to YouTube and enter in metadata.

Future me will thank past me for giving future me all this nostalgia material, and I could use these recordings to:

Putting it on YouTube will also mean it won’t cost me any local storage space - everything is offloaded over to Google’s data centres. However, this does mean losing video quality due to the server-side transcoding. As advances in data storage technology causes significant drops in price and efficiency, I want to eventually keep the lossless recordings, but for the older recordings on YouTube, downloading a lossy compressed copy off YouTube is the best I can do (unless Google miraculously provides original-quality lossless copies in the future.

Although I can put the videos on YouTube publicly, it doesn’t have to be public; I can keep them private, or unlist them for privacy. However, making them public can be great for sharing my experiences, for anyone who cares to watch.

However, that assumes anyone even cares to look. It’s certainly not out of the question that an entire massive archive of raw gameplay footage may never get any views for however long Google decides my videos can be kept for (centuries?). But even if no one watches my videos, I lost nothing.

Unfortunately, putting all this gameplay footage online may be information that could be used against me one day.

Picture this: perhaps one day, I might promise someone to do a certain task at home, but if I don’t get it done (or maybe even if I do), me dumping large amounts of gameplay onto YouTube could be used against me, with accusations along the lines of “if he wasn’t so lazy, this could’ve been completed”, or “if he wasn’t so lazy, this could’ve been done better”.

Someone could also use my video uploading patterns for malicious purposes, such as for planning break-ins.

All of these concerns are also shared with actual professional streamers (such as on Twitch) and professional YouTubers, so I could borrow some of their wisdom.

For instance, I’ll need to ensure that I allow no personal information to leak into my videos. This can be easy if I’m gaming on my own, but it can be more of a problem when I’m casually playing with friends with voice chat. We don’t necessarily always talk about our personal lives, but occasionally, we can get things like:

I’ll also need watch my uploading schedule. Highly frequent video postings can indicate that I’m having a long break from work or school, while gaps in my upload schedule can indicate when I’m heading out for work/school, or if I’m on a long trip overseas (or even domestic). All of these things could be leveraged by someone with the wrong intentions.

Without a recording going on, I’m naturally more relaxed, knowing that everything that’s happening is kept to myself, and I can go as crazy as I want. No one will know.

While recording, I find that there’s added pressure to maintain privacy while also being presentable to the outside world. This can cause undesirable behavioural pattern shifts, such as increased stiffness and acting nervous as though one is in front of an audience, or otherwise simply not acting “natural”. This may also reduce the enjoyment of a videogame.

Sure, I’m not necessarily making these videos for others, but I don’t want to produce something that may be looked on in disgust one day, even if the video is private and the only person who will know is myself.

And even if I’m not the problem, it can be a problem for other people if they’re in the game with me (especially if voice chat is on). Even if people never say that they mind, I’ll still be worried.

I’ve gotten a bit negative with those last two discussion points, so I’d like to discuss a more positive one: satisfaction of producing content with my time.

This is a lot of why I’m maintaining a blog. Content creation is satisfying because I want to produce things for others. Ideas and experiences are great, but sharing them is even better. So why not extend it to gaming? Gaming is already satisfying for the moment-to-moment experiences, so why not try to capture it?

I personally feel that knowing my experiences are captured by screen recording and being intentionally (by myself) saved somewhere is satisfying. My time feels much more well-spent if I produce things, no matter how mundane (such as raw gameplay videos), and I feel more productive while playing videogames this way.

And who knows, maybe I might actually end up building an audience and pivot into producing “proper” gaming content? I’m not exactly sure how that might happen, but then again, I’m not sure many of today’s successful YouTubers in the gaming category knew either. That could be an even funner yet productive way of spending my leisure time while also making a bit of extra money on the side.

It’s an attractive idea, yet also surprisingly complicated. For me, I think I’ll continue exploring this idea of uploading gameplay, although I’ll probably end up uploading the majority of them as private YouTube videos.

2018-05-04

For distributed systems class recently, we had to write a simulated distributed network in Erlang.

The assignment involved getting a whole bunch of Erlang processes (which are basically really lightweight threads) to send messages to each other according to the specification. It had a bit of a convoluted way of doing things, but it was intentionally to produce a model that demonstrated an important concept in distributed systems, albeit without the additional complexity layers of socket programming and networking.

I ended up with a bug that wasted an embarrassing number of hours, which got me slowly stepping through a very substantial portion of my program’s functionality in reverse. The entire program culminated into one process producing a small amount of outputs. Being a simulation of a distributed system of several concurrently running nodes, this meant tracing through a web of message-passing.

A lot of the time wasted during debugging was actually due to poor assumptions I made about how the system worked. That’s an entirely separate epic fail on its own (see the appendix section), but that’s not the focus of this particular post.

It turned out that towards the beginning of the entire message exchange, I made a one-character typo. This would’ve been caught instantly with good programming practices.

I’m kinda a super-noob at Erlang and functional programming in general. I literally crash-coursed it over the course of an hour. If I’ve completely missed the mark on something, feel free to yell at me at [email protected].

The erroneous Erlang code took the following form:

if

Foo =:= commited ->

doSomething();

true ->

doSomethingElse()

end,This is basically equivalent to the following pseudocode if-else:

IF (Foo == commited) THEN

doSomething()

ELSE

doSomethingElse()

END IFThe Foo variable was only expected one of two possible atom values: committed or abort. Because of the typo, doSomethingElse() was always executed, even if doSomething() was meant to be executed instead.

If you’re not familiar with Erlang’s atom type, you can just think of them as a big global enum, and atoms are used in place of things like boolean types, magic number constants, and enum types as seen in other languages. For example, instead of the boolean type, we use the atoms true and false.

From the programmer’s perspective, atom literals can look somewhat like string literals. This makes them particularly susceptible to typos that only get tested during runtime.

Though, using error-prone language constructs doesn’t have to be this painful. All those hours wasted debugging could’ve been solved using one simple technique: writing fast-failing code.

What I should’ve done in my assignment is the following:

case Foo of

commited ->

doSomething();

abort ->

doSomethingElse()

end,Here, the variable Foo is pattern-matched against the atoms commited and abort. If the case statement fails to find a match, it raises an exception:

Eshell V9.3 (abort with ^G)

1> Foo = committed.

committed

2> case Foo of

2> commited ->

2> doSomething();

2> abort ->

2> doSomethingElse()

2> end.

** exception error: no case clause matching committedWith this version of the code, the error immediately makes itself known, and I would’ve fixed the typo and moved on with my life.

Different languages work differently, so let’s have a look at a similar example in Python. Suppose we had a string that is expected to only be either "committed" or "abort". A fast-failing solution is the following:

if foo == "commited":

do_something()

else:

assert foo == "abort"

do_something_else()Here, the assert checks that if the else block is entered, foo indeed does have the correct value. This would’ve caught the typo in much the same way as our Erlang solution:

>>> foo = "committed"

>>> if foo == "commited":

... do_something()

... else:

... assert foo == "abort"

... do_something_else()

...

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 4, in <module>

AssertionErrorHowever, assert will not work with the -O flag, so if you absolutely have to raise an exception in production, it should be checked in an elif block and an exception raised in the else block:

if foo == "commited":

do_something()

elif foo == "abort":

do_something_else()

else:

raise ValueError("Unexpected value for foo.")If you haven’t been using fast-failing code before, I hope I’ve convinced you to start using them now. However, fast-fail goes so much deeper than the scope of this post.

For example, asserts are highly versatile in verifying the state of your program at specific points in the code while also usefully doubling as implicit documentation. The following example shows asserts being used to check function preconditions:

def frobnicate(x, y):

assert x < 10

assert isinstance(y, str) and ("frob" in "y")

...Though, fast-fail is desirable in production, and asserts are usually not checked in production. There are many different practices for raising and handling errors, especially for critical applications such as aeronautics and distributed infrastructure. After all, you wouldn’t want your million-dollar aircraft exploding shortly after launch due to a missing semicolon, or your entire network of servers failing just because one server threw an error.

And of course, I haven’t even touched the ultimate in fast-fail: compile-time errors (as opposed to runtime errors), and statically typed languages (as opposed to dynamically typed languages).

You can certainly still use the Erlang if-statement like so while still failing fast:

Eshell V9.3 (abort with ^G)

1> Foo = committed.

committed

2> if

2> Foo =:= commited ->

2> doSomething();

2> Foo =:= abort ->

2> doSomethingElse()

2> end.

** exception error: no true branch found when evaluating an if expressionHowever, I personally wouldn’t recommend it for this particular use-case (or even the majority of use-cases) since the case statement here is much clearer, concise, and less error-prone to write.

It should of course also be noted that this is a quirk specific to Erlang. Python would just skip right over the if-statement:

>>> def f(x):

... if x == "commited":

... print("bar")

... elif x == "aborted":

... print("baz")

... print("foo")

...

>>> f("commited")

bar

foo

>>> f("committed")

fooBe sure to learn the behaviour of your particular language when trying to write fail-fast code.

Also, Python unfortunately lacks such a cases statement, though techniques such as the use of a dictionary may be used if it makes things clearer. The Python dictionary also usefully throws an error if no such key exists:

>>> def f(x):

... {

... "commited": lambda : print("bar"),

... "abort": lambda : print("baz")

... }[x]()

... print("foo")

...

>>> f("commited")

bar

foo

>>> f("committed")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 5, in f

KeyError: 'committed'I did mention that the way I went about debugging my assignment was its own epic fail, but it’s not particularly deserving of its own separate post so I’ll summarise it here in case it’s of interest to anyone. As a warning though, this explanation might be a bit abstract, and I really don’t blame you if you don’t get it. I’m writing this here for completeness.

Each node in my simulated network potentially spawns a bunch of processes (which I will call “mini processes” for convenience) which it kills only if the network decides to return “abort”. If the network decides to return “committed” instead, the network doesn’t touch them.

These mini processes in my test case receive messages from a controller process after the network makes its committed/abort response.

However, I was finding that despite the network returning “committed”, the messages from the controller process didn’t seem to reach the mini-processes. Or perhaps more accurately, when I put print-statements in the mini-processes, expecting them to all print messages to the terminal, nothing was printed.

Not knowing any better at the time, I focused intensely on why messages sent from one process may not reach a target process.

It took me far too long to realize that the bug as detailed in this blog post caused all nodes to instantly kill all mini-processes since the “abort” code was always executed. The mini-processes were always killed before they could receive the controller’s messages.

Always challenge assumptions, kids.

2018-04-28

Lately, I’ve been starting to get back into writing content for this blog, and with that, my perspective on blogging has changed slightly. I’d like to discuss that briefly in this post.

I created this blog to share my views and ideas on various things, all in one place. However, I previously felt like I wanted to achieve some minimum level of “quality”. I wanted this to be a place where if someone were to subscribe, I can give my personal guarantee that they will be reading top-quality, highly-relevant and super-interesting content each and every time I release a new post.

However, wanting to have a high bar of quality I find gets in the way of getting any amount of content out. I’m finding that it leads to chronic procrastination with starting posts, and not to mention the amount of time I spend on any single post, focusing far too much on writing and editing.

And even despite my best efforts to achieve my ideal, I still believe my blog is far from achieving it. Ultimately, all that procrastination and extra writing/editing time has only been wasted. My posts are terribly rambly, my grammar and organization of ideas are lacking greatly, I can get hand-wavy, etc.

So even if I wanted to produce “quality”, I honestly don’t really know how to achieve that right now. I’m not a writer by trade, and I even practically failed highschool English. My grammar will need a huge amount of work, and since I don’t write much, I don’t really have a lot of experience structuring my thoughts and my communication. Sure, I’ve always read a tonne of articles on the internet, but I never really cared about learning how other people structure their writing until now; I just cared that I absorbed the ideas.

As such, I’ve resolved to divorce my previous idea of “quality”. Rather than achieving that elusive “perfect”, “good enough for me” will be my goal. Of course, that’s never a valid excuse to never try to achieve some level of quality, but my focus will instead be on writing for the fun of it, writing what I want to write, and getting ideas out.

Quality should hopefully come naturally over time as I continue this blog.

As I write, I’m constantly reassessing my grammar. If I’m unsure of something, I Google it. In fact, just a minute ago, I Googled et cetera and how the abbreviation etc. is used in writing. I’ve Googled grammar a lot with all my posts, and I hope that continuing to write and learning about grammar and writing this way will naturally lead to an accumulation of knowledge and improvement.

My skill and instinct as a writer should hopefully also continue to improve as I get content out. By getting into the habit of writing, I want to practice identifying cool ideas I want to share with the world, developing habits that help me seek and retain key ideas, developing a better sense of how to structure my ideas in writing, and generally writing faster (rather than taking my time to agonize over how to write).

Structuring my thoughts and building mental habits is also a skill that I want to improve in general. Being kinda a shut-in of a person at the moment, I hate to admit it but my communication skills in general just absolutely suck. Writing should help offset my problem, helping me to eventually integrate into becoming a productive member of society.

For now and hopefully continuing far into the future, I hope to keep using this blog as a “me-blog”. I write because I’m fed up of keeping my thoughts and ideas quietly to myself, and I just want to get them out in some fashion. Thoughts, ideas, and experiences are incredibly valuable yet ephemeral, so I want to capture them in the moment. Not putting them down on record is a damn waste of potential. Someone could’ve been inspired by them!

Now, continually producing content in the way I described is cool and all, but I still want to produce resources one day that meet the “ideal perfect” that I described earlier. My plan is to maybe one day restructure my current blog to sectionalize it, or create new blogs which I might purposefully use for heavy-hitters, or more specific topics. But that’s something for another time.

To hopefully get my content a bit more visibility, I’ll be looking into using Twitter and Reddit to link back to and promote my blog.

I’m a bit of a nooblet when it comes to Twitter though, so let’s see how well this goes…

2018-04-26

In my second year of university, I took a class that involved a series of AVR assembly language programming labs. One of them required an implementation of a queue data structure. It was meant to be a simple lab, but an early design decision made it needlessly complicated. This additional complexity single-handedly turned debugging into a nightmare.

My implementation required that all elements be butted up to the front of the buffer. One pointer points to the back.

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| A | B | C | | | |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackEnqueueing items would add to the back of the queue, and the Back pointer is updated in the process:

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| A | B | C | D | | |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackDequeuing would require us to take from the front and shift the remaining elements forward to fill in the space:

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| B | C | D | | | |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackHopefully it should be obvious that this makes dequeuing so expensive to accomplish (O(n)) since you’d have to read and write across all the remaining elements in order to do the shifting.

This mistake of choosing the wrong queue implementation bloated the code up by requiring an unnecessarily complex dequeue function to be implemented, and since the function didn’t work the first time around, it took at a nightmarish night of debugging.

The program was failing in such weird ways, and there were so many other possible points of failure, with so many subsystems concurrently running and accessing data all at once. Remember, this is assembly language we’re talking about! If the dequeue function were simpler, I could’ve quickly “proved” that it works as expected, thus allowing me to focus on other places.

In the end, the dequeue function was the problem.

When I proudly presented the final working program to the lab demonstrator, while he was impressed that I got such a thing to work, he was shocked that I even attempted to implement such a thing in the first place. “You realize you could’ve implemented this with a circular buffer, right?”

In a circular buffer, your queue contents are continguously contained somewhere within the queue, not necessarily at the front or back. Two pointers point to the beginning and end.

Front

v

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| | | A | B | C | |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackDequeuing would simply grab whatever’s at the front and update the pointer:

Front

v

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| | | | B | C | |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackAnd enqueing would simply add to the back and update the pointer:

Front

v

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| | | | B | C | D |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackIf the end of the buffer is reached, we simply wrap to the end, using modular arithmetic to start reading from the beginning again:

Front

v

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| E | | | B | C | D |

+---+---+---+---+---+---+

^

BackSimple and fast!

The really obvious takeaway here is to make sure you evaluate your data structures and implementations properly, otherwise you end up giving yourself so much pain later on.

But for me personally, I think at the time, I was a bit too dangerously relaxed about the whole topic of data structures. At that point, I never experienced just how much worse poor design decisions can make everything.

To me, this was a painful yet valuable lesson in ensuring the suitability of a design, and it highlights the importance of mastering and internalizing understanding of data structures and algorithms.

2018-04-25

Web-based RSS readers are convenient for being a complete online service, but local RSS readers can offer their own advantages. So if you’re looking to get the best of both worlds, here’s my solution.

I use Inoreader as my cloud-based RSS reader, and Newsboat as my local RSS reader.

In summary, the whole thing works using three things:

However, this scheme has a problem: I can’t structure my subscriptions! Newsboat only exports a single OPML file, and OPML doesn’t support tags (or similar constructs), so all that structure is lost when Inoreader reads the OPML file.

To solve that problem, I also wrote a script to separate the original OPML file into separate OPML files (one for each tag).

So how does everything work?

(Note: I assume basic familiarity with Inoreader, Newsboat, Git, GitHub, and automation/scripting.)

OPML is a file format that contains a list of web feeds. These are often used to export/import RSS subscriptions between different RSS readers.

For example, if you’re using Feedly and you one day decide you want to switch to Inoreader, you can download all of your subscriptions from Feedly to your computer as an OPML file, then upload that file to Inoreader. Inoreader now has all your Feedly subscriptions.

Here’s an example OPML file:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<opml version="1.0">

<head>

<title>newsboat - Exported Feeds</title>

</head>

<body>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="http://simshadows.com/feed.xml" htmlUrl="http://simshadows.com//" title="Sim's Blog"/>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="http://kuvshinov-ilya.tumblr.com/rss" htmlUrl="http://kuvshinov-ilya.tumblr.com/" title="Kuvshinov Ilya"/>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="https://xkcd.com/rss.xml" htmlUrl="https://xkcd.com/" title="xkcd"/>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/feeds/posts/default" htmlUrl="https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/" title="Google Project Zero"/>

</body>

</opml>Normally, your Newsboat subscriptions are stored in the ~/.newsboat/urls file. Mine can be found here.

To export everything into an OPML file, run the following command:

newsboat -e > ~/subs.xmlMy exported OPML file can be found at https://github.com/simshadows/sims-dotfiles/blob/master/dotfiles/newsboat/autogenerated-opml/ORIGINAL.xml.

When you add an OPML subscription to Inoreader, it periodically pings a URL containing an OPML file to monitor it for changes, which keeps your Inoreader subscriptions synchronized with it. This is literally the same basic principle in which RSS works!

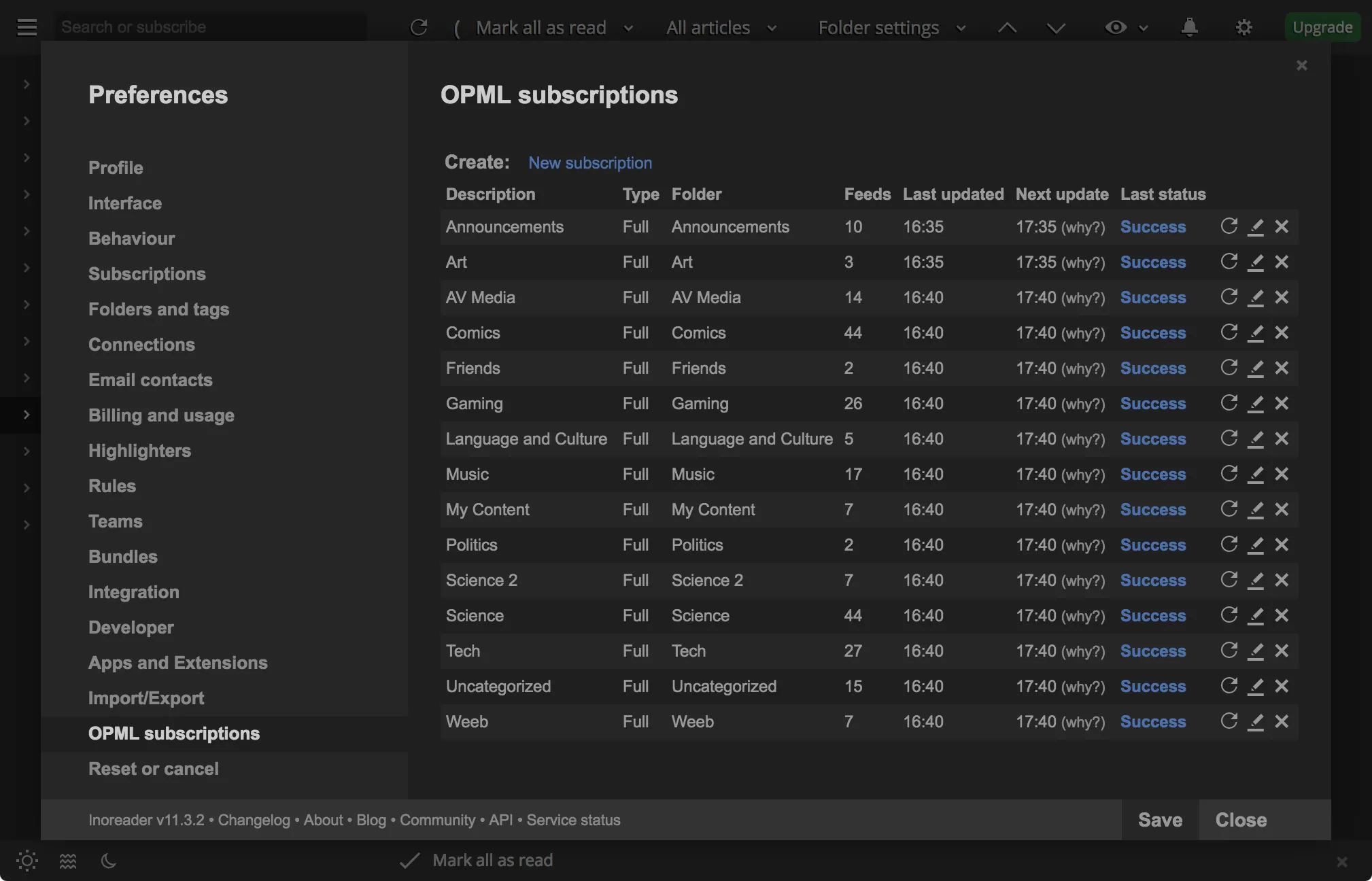

Here are my OPML subscriptions at the time of writing:

Each OPML subscription in Inoreader is associated with a particular tag.

In order to use Inoreader’s OPML subscription on our Newsboat OPML export, we need a way to host the OPML file on the internet. This is where GitHub comes in.

With Github, just git push your file up to your public repository, and grab the URL to the *RAW* file and subscribe to it with Inoreader. Every time you update, git push again and Inoreader automatically updates your Inoreader subscriptions!

You can find my raw OPML file at: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/simshadows/sims-dotfiles/master/dotfiles/newsboat/autogenerated-opml/ORIGINAL.xml

As I mentioned before, you lose the tag structure from the ~/.newsboat/.urls file if you just use the raw OPML export from Newsboat, and I solved the problem with a script that separates the original OPML file into separate OPML files (one for each tag).

All the script does is:

~/newsboat/.urls file for tags.For example, if we start with the following ~/.newsboat/urls file:

https://www.nasa.gov/rss/dyn/breaking_news.rss "Science"

http://www.folk-metal.nl/feed/ "Music"

https://myanimelist.net/rss/news.xml "Weeb"And we the following OPML file:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<opml version="1.0">

<head>

<title>newsboat - Exported Feeds</title>

</head>

<body>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="https://www.nasa.gov/rss/dyn/breaking_news.rss" htmlUrl="http://www.nasa.gov/" title="NASA Breaking News"/></body>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="http://www.folk-metal.nl/feed/" htmlUrl="http://www.folk-metal.nl" title="Folk-metal.nl"/>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="https://myanimelist.net/rss/news.xml" htmlUrl="https://myanimelist.net/news?_location=rss" title="News - MyAnimeList"/>

</opml>To generate an OPML file for the Music tag, we simply copy over the original OPML file while deleting all unrelated entries, like so:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<opml version="1.0">

<head>

<title>newsboat - Exported Feeds</title>

</head>

<body>

<outline type="rss" xmlUrl="http://www.folk-metal.nl/feed/" htmlUrl="http://www.folk-metal.nl" title="Folk-metal.nl"/>

</opml>It’s really that simple! Just subscribe to each separate OPML file on Inoreader.

My implementation is technically actually split between two scripts:

However, I wrote these scripts to fit my repository’s style (and the code’s not very robust), so I suggest you write your own.

You can also find my OPML files for each tag here: https://github.com/simshadows/sims-dotfiles/tree/master/dotfiles/newsboat/autogenerated-opml

2018-04-08

Potato crisps (and similar snacks such as cheese twisties and corn chips, which I will refer to blanketly as crisps) are often greasy or otherwise messy to eat without utensils and other tools. Sure, you could just decide to not eat them while doing your term paper or playing videogames, or you could just suck it up and resign to the completely avoidable fate of getting your keyboard, mice, and books covered with food grease. Or, you could actually use a practical solution.

Chopsticks are long and can reach deep into the bag. They’re nimble and have the ability to pick up large crisps, or bunches of various-sized crisps as needed. They make minimal surface contact with the food, but even if the ends get greasy with seasoning, simply run a single segment of toilet paper down the length of the chopsticks twice per stick (assuming you use smooth reusable chopsticks). Now, they’re clean enough to rest back down to be used again for the next bag.

Chopsticks are of course not just limited to crisps and your more “traditional chopstick foods” such as ramen and dumplings. They’re great for anything else bite-sized: potato chips, chicken nuggets, Turkish pide, and sometimes even chicken wings (although those tend to be a lot more challenging to clean up around the bone), and many others are completely practical to eat with chopsticks.

Other solutions certainly exist and can also be effective (usually depending on the nature of the snack). But for me, although it can look a bit silly, nothing beats the fine control, swiftness, and cleanliness of chopsticks.

2018-03-27

For Web Application Security class last year, most of the final exam was an open-book, open-internet practical: we were given a remotely hosted web application to play with, and we had to obtain flags. No flag meant no mark.

My prepwork involved making a PDF document using Latex containing all the written notes I needed. This was of course supplemented by other resources such as my archive of homework solutions, lecture slides, textbooks, etc. A key component of that Latex document of course was code that could be copy-pasted when needed.

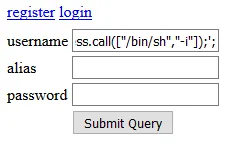

The problem with that code, however, is that it’s not like a program you’re meant to compile and run locally, otherwise a compiler or interpreter would’ve caught the issue and issued the relevant warnings for the problem, allowing it to be resolved quickly. Instead, the code is often pasted directly into input text fields of a web page like so:

Or, the significantly better method of using Burp Repeater and other such tools:

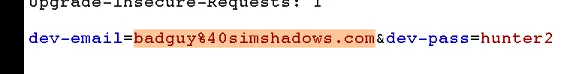

In the above screenshot, the raw input data can be observed and modified here:

After sending off the input data to the remote server, feedback produced by the server may be limited and you may have to infer the web application’s state from minimal information. After all, web servers and applications are ideally designed to withstand attacks from the outside which look to coax the app/server into doing something to the attacker’s advantage. Intentionally hiding unnecessary information about the system is one of many tricks defenders use as part of the overall defense strategy.

In reality, the amount of relevant feedback emitted by the web server/application can vary significantly, depending on many aspects of the system. However, the fact still remains: A lot of the time, you’re swinging in the dark until you catch something. You may catch plenty, you may catch none, or you may even catch bait or misleading responses.

In my case, despite having revised and practiced extensively before that final exam practical, I got zero flags. Even more painful was how I spent the two hours trying every trick and variation I knew, and feeling like I knew exactly what the solution should be for all flags that didn’t require knowledge of other flags, yet nothing did anything interesting. I kept thinking I missed some detail about the web application and continued to think along those lines.

After the exam was over, I got a colleague to show me a flag. She got two of them instantly. (I think the application was taken down before we could try more flags.)

That afternoon, I found my text document full of payload code I made during the exam. A lot of the quotation marks were found to be Unicode, as an artifact of my PDF document compiled from Latex. All my payloads were based off text copied from that PDF document. Although I can’t confirm, that was most likely the reason my payloads failed to make the web application budge one bit. If I just used ASCII quotation marks, I would’ve gotten at least a few flags.

By Unicode quotation marks, I’m referring to the quotation marks that are not part of ASCII.

The ASCII quotes (including the grave mark) are:

Hex Unicode Raw Description

----------------------------------------------------

0x22 U+0022 " QUOTATION MARK

0x27 U+0027 ' APOSTROPHE

0x60 U+0060 ` GRAVE ACCENTThe quotation characters above are the ones that are typically intended for the computer to parse with special meanings that are important in all aspects of a programmer’s work.

The following is a subset of what I consider to be the “Unicode quotation marks”:

Unicode Raw Description

----------------------------------------------------

U+2018 ‘ LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION MARK

U+2019 ’ RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION MARK

U+201C “ LEFT DOUBLE QUOTATION MARK

U+201D ” RIGHT DOUBLE QUOTATION MARK(Note: Technically, ASCII is a strict subset of Unicode blocks, hence ASCII characters are also Unicode characters, but Unicode characters are not all ASCII characters.)

These “Unicode quotation marks” are intended to be more typographically accurate than ASCII quotes (which appear straight compared to the curliness of Unicode quotes). They are not typically meant to be interpreted by computers in place of Unicode quotes.

In my case, the ASCII quotes I used in the Latex document were converted to Unicode quotes in the compiled PDF. Word processors (such as Microsoft Word) will often similarly convert quotes. Other applications (such as email) may also convert quotes. All of this is done to make the final document visually pleasing and typographically correct (much to the detriment of computing professionals out there).

You may have also noticed that this blog post’s quotation marks may have been converted into Unicode quotation marks (except in code blocks). Assuming I haven’t changed things too much since the time of writing, these blog posts are sourced from files written in Jekyll Markdown, and here, I use ASCII quotes.

Further reading:

Even beyond things like rendered PDFs, Microsoft Word, and HTML web pages, you may run into the issue in simple plaintext files (such as if someone simply copy-pasted text in from Microsoft Word or a PDF, like during my web application security exam). Unicode quotes can come in from anywhere when you least expect it.

This is one of those things where the best you can do is be aware and have it at the back of your mind, and hopefully this blog post has given you that awareness. Next time you run into a cryptic problem with seemingly no obvious reason, Unicode quotes may be worth considering.

It really doesn’t take much to go beyond and find more problems related to using different characters that look visually similar (or the exact same). For instance, a popular example of this problem set is the “GREEK QUESTION MARK” (U+037E)”. This character is visually similar to the semicolon character (;), and is often used as an example of a prank that can be used on programmers (such as this Stack Overflow post).

In the context of security, the exploitation of such a mechanism is called a homograph attack. IDN homograph attacks for instance can be used to trick users into believing they’re browsing www.apple.com when in fact they are browsing xn—80ak6aa92e.com (that link is not malicious at the time of writing, and was made to harmlessly illustrate the dangers of this IDN homograph vulnerabilities).

Further Reading:

As for me, I took a supplementary exam for web application security class several weeks after the original exam. Needless to say, I made doubly sure I had properly formatted (with ASCII characters) code the second time around. My unicode quotes problem was no more.

2018-03-23

I’ve chosen to do the majority of my development work in a VirtualBox VM running an ultra-lightweight configuration of Arch Linux, with the VM typically running fullscreen or in a large window. All my files are in the virtual disk, I use a text editor inside the VM, and all of my tools are in there.

It works beautifully for me, but for many, native development is suitable enough. Running natively has the distinct advantage of performance, tools for practically all popular needs exists on all major platforms, and you often won’t need to mess with the environment too much anyway once you’re established. Even the barrier to developing for Linux systems on Windows is largely lifted thanks to Vagrant, Docker, or possibly even WSL.

And for some, native development will be the most sane option, particularly if hardware access is required as GPU access can be difficult and I/O may be poor. For instance:

So if that’s you, you know who you are. There are solutions (such as this), but I haven’t had a chance to play around with them yet.

However, there are many interesting advantages that make a VirtualBox Linux VM well worth considering if it works for your workload.

Note: I’ll be talking more on the pros and cons of the virtualization side of things rather than diving too specifically into my Linux setup.

Not really a point I’m arguing for (hence “Advantage 0”), but it’s most certainly a plus!

For Windows users, I think this is the most important point. With a VirtualBox Linux VM, there is no need to wrestle with your native OS to get something working, and you dodge a lot of the weirdness and tech-acrobatics that can be required. Yes, it can work if you tried hard enough, but sometimes it’s nice to simply not have to go through that.

On top of that, you’ll be working on literally Linux. If you’re a Windows user taking computer science classes in college and your class requires you to program in C on a Unix-like system, this can save many headaches while at the same time familiarizing you with the same environment everyone else is using.

Or if you, like me simply prefer working in Linux but for various reasons have to install Windows or Mac OS natively on your machine (such as to game on Windows or to reap other benefits Windows and Mac OS have over Linux), you can still feel right at home.

Not only does the VM work, but it generally works wherever the latest version of VirtualBox is supported.

This is particularly awesome if you have multiple machines and you want to work on all of them. In my case, I have a Windows-based gaming desktop machine and a Macbook Pro, and I simply copy the VM files between them as necessary. (I only bother copying the VM after major system changes thanks to git.)

Everything moves, so the result is that it works and looks practically exactly the same, everything from your text editors to your tools, your files, and your perfectly arranged directory structure. Everything works exactly how you like it. No need to somehow match certain settings between your computers, no need to resolve mismatched compatibility. And with the massive amount of customizability and choice in Linux-land, all those tweaks you made? Yep. They all stay with your VM.

Reformatting and reinstalling your host OS is also made simpler since you don’t have to bother as much about your development environment; just reinstall VirtualBox and copy your VM back in. I’ve had to do that to resolve sluggish performance on my Mac.

The state of your entire machine can be versioned so you can go back to a different point at any time.

To me, this has two broad but important implications.

First, it allows you to recover faster from a broken system. However, this assumes that you create snapshots regularly. In my case, I generally make snapshots between major system changes, after successful whole-system updates, or major /home directory structure changes. Since I use git and put repositories on GitHub quite liberally, I don’t really bother too much if I lose changes within repositories after being git pushed.

Second, snapshots enables experimentation, which I think is important for users learning how to use Linux (such as myself!). Snapshots can even be taken while the machine is running, so simply taking snapshots at key points will allow you to try new things, observe the effect, and easily recover if you end up breaking your system.

Snapshots do take host disk space though, so I only keep two snapshots into the past (deleting old ones), and I don’t “fork”.

This can be a huge boon if you like tinkering and exploring, in case you mess something up or if you accidentally run malware or get hacked. Everything that happens inside the VM stays in the VM. If the VM crashes, it probably won’t mess up your host OS.

(Do remember though that this isolation is not perfect. It does however make things increasingly difficult for attackers.)

(Also, your VM may not be guarded against consuming your computer’s resources, so your computer may freeze if you hit it too hard. That should be obvious, but I’d like to mention that for clarity.)

I’ve already touched on this in my discussion of snapshots, but all of these points so far are great for experimentation. I don’t think I need to explain any further.

Depending on who you ask, the fact that you’re running Linux can be a huge advantage or disadvantage.

In my case, I absolutely love using Linux, so I’ll list it as an advantage. (I’ll probably write more on this in the future, so I’ll leave it at that for now.)

Such awesomeness unfortunately comes with a few major downsides that can make or break the entire experience.

I’ve already mentioned this earlier: while the system works excellently from within, I’ve had major difficulties getting the VM to interface and work with USB (VirtualBox USB passthrough has been unusably unstable for me), and I suspect GPU isn’t so smooth sailing either with VirtualBox.

However, there are probably better solutions out there (or maybe VirtualBox’s USB drivers are fixed). I haven’t really looked into it so if you find something, I’d love it if you could let me know!

It should be obvious that VMs come with performance penalties. Your VM will be eating up a portion of your CPU, memory, and potentially your entire graphics card.

However, I find my experience to be pleasantly smooth (no noticeable performance penalties) with the following settings:

These settings work perfectly on my late-2013 Macbook Pro with 8GB of RAM (and it even supports me using both a Linux VM and a Windows 7 VM concurrently!), but it may not work on your machine, especially if your VMs aren’t configured to be as lightweight as mine. As such, your mileage may vary.

If you want ballpark numbers though, my (untested) advice is to have a minimum of 8GB of RAM in your computer in order to be comfortable using a VM. Otherwise, any decent 2-core laptop manufactured after 2012 will probably serve you fine.

(Or, you could just test performance on your machine anyway since VirtualBox and Linux are free :)

My Linux VM takes 34.86 GB at the time of writing, but it can be much smaller. Within the Linux VM, I’m only using 20.9 GB.

That consumed space is barely felt in my 256 GB Macbook though, and I suspect that might be the same with many others users.

As for the additional 14.0 GB of virtual disk bloat, I suspect it comes from several places:

There is a way to lessen the impact of point #3 by “compacting” the filesystem and zeroing unallocated blocks, but that can be a hassle. I don’t even bother anymore.

(For reference: My Windows 7 VM takes 51.28 GB, and it’s basically a fresh install!)

Generally, sensitive data is protected by preventing users’ direct access. I’m not just talking about your business documents and various embarrassing selfies; the software itself and various cryptographic secrets can be stolen or tampered. Having a full VM sitting on disk on your host OS and accessible through your user (as opposed to needing administrator/root access) opens you up to a variety of potential attacks. For instance:

A possible solution is to enable virtual disk encryption. This should make it exceptionally more difficult to “smash-and-grab” from the disk, though it’s not perfect since keyloggers and other techniques can still be used to circumvent it.

In practice, it may not matter too much as long as you have good security practices; if your user is compromised, it’s probably just a matter of time before they gain deeper access to your machine. However, it pays to be a bit paranoid.

(I’d also like to clarify: You probably use disk encryption with your host OS, but that can only help against physical theft of your computer (and even then, it’s not necessarily perfect). You will still need to encrypt your virtual disk in order to mitigate those attacks I mentioned above.)

Unfortunately, having a VM also means another system for you to maintain. However, that may not actually be that bad. This is a great way to learn Linux!

Perhaps everything is working perfectly fine for you developing in your native OS, so it can be difficult to see why you should move to a VM.

However, maybe consider trying out a VM anyway. Trying new tools in general is a great way to learn new things and improve your workflow!

Hopefully I’ve provoked some ideas on the possibilities with virtualization. However, you may still be wondering: Why Linux?

After all, the entire GNU/Linux ecosystem is the other major part to consider if you want a VirtualBox Linux VM.

I’ll leave that for another post.

2017-10-25

For neural networks class, a major component of the second assignment was to build and train a recurrent architecture. At this point, I haven’t really had a tonne of experience with the TensorFlow framework. Although I’ve implemented some simple networks, I haven’t done something involving recurrent architectures before, so I consulted various tutorials.

With these tutorials, my overall approach of starting with a rough sketch in code I think makes sense when learning a new framework: You build a rough version that seems to represent what you aim to do, then you iron it out to get your first super-basic running version. Figure out what it’s doing, then iteratively build on top of it. Ideally, this would mean going back to the framework documentation and seeing if all the pieces work as you expect.

Unfortunately, somewhere along the way, I had the brilliant idea of blindly using a TensorFlow function without reading the documentation, and continuing on to assume it to be correct. Testing raised an exception.

And on debugging that exception, I made the assumption that if a function call doesn’t raise an exception, then I used the function correctly.

Working from these assumptions, I wasted a lot of time attempting various things and reading different tutorials. With nothing working, I then moved on to reviewing all the relevant theory from the lectures to ensure I completely understood everything. But even after that, I couldn’t figure out what was wrong with the code, so I spent more time reading various articles on the design of the TensorFlow framework. Nothing gave me an answer, which left me beyond frustrated.

But as it turned out, the function call raising the exception was fine. The problem was that I used another function incorrectly in an earlier part of the code. Despite using that function incorrectly, no exception was raised until later on.

In the version before fixing the error, I had the following two lines as part of the graph definition code:

lstm = tf.contrib.rnn.BasicLSTMCell([BATCH_SIZE, WORD_COUNT])

rnn_outputs, states = tf.nn.dynamic_rnn(lstm, input_data, dtype=tf.float32)When run, the first line seems to run fine while the second line raises an exception that seems unrelated to my own code, and rather a bug in TensorFlow:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "train.py", line 41, in <module>

imp.define_graph(glove_array)

File "/home/simshadows/git/cs9444_coursework/asst2stage2-sentiment-classifier/implementation.py", line 154, in define_graph

rnn_outputs, states = tf.nn.dynamic_rnn(lstm, input_data_expanded, dtype=tf.float32) # , time_major=False

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn.py", line 598, in dynamic_rnn

dtype=dtype)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn.py", line 761, in _dynamic_rnn_loop

swap_memory=swap_memory)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/control_flow_ops.py", line 2775, in while_loop

result = context.BuildLoop(cond, body, loop_vars, shape_invariants)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/control_flow_ops.py", line 2604, in BuildLoop

pred, body, original_loop_vars, loop_vars, shape_invariants)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/control_flow_ops.py", line 2554, in _BuildLoop

body_result = body(*packed_vars_for_body)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn.py", line 746, in _time_step

(output, new_state) = call_cell()

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn.py", line 732, in <lambda>

call_cell = lambda: cell(input_t, state)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn_cell_impl.py", line 180, in __call__

return super(RNNCell, self).__call__(inputs, state)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/layers/base.py", line 450, in __call__

outputs = self.call(inputs, *args, **kwargs)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn_cell_impl.py", line 401, in call

concat = _linear([inputs, h], 4 * self._num_units, True)

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn_cell_impl.py", line 1021, in _linear

shapes = [a.get_shape() for a in args]

File "/home/simshadows/.local/lib/python3.6/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/rnn_cell_impl.py", line 1021, in <listcomp>

shapes = [a.get_shape() for a in args]

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'get_shape'The problem in the code above is that tf.contrib.rnn.BasicLSTMCell() takes an int as the first positional argument, not a list. (See the __init__ arguments in this page of the documentation.)

The version after fixing the error (simplified) looks like the following:

lstm = tf.contrib.rnn.BasicLSTMCell(HIDDEN_SIZE)

rnn_outputs, states = tf.nn.dynamic_rnn(lstm, input_data, dtype=tf.float32)With duck-typing in Python, that previous function call didn’t raise an exception. This was because the operations performed with the bad argument value were by chance supported by that bad argument value.

However, having the bad argument work doesn’t mean we can get away with it. The bad function call can break a class invariant, meaning that the state of the object is no longer guaranteed to be valid.

With the state of the object now potentially invalid, the behaviour of operations on or with that object will now be undefined, and can raise weird exceptions that can be difficult to trace back to the bad function call.

To illustrate what this means, let’s look at a simple example.

IncrementorConsider the following class definition:

class Incrementor:

def __init__(self, value):

# value is an int.

self.value = value

def change_value(self, value):

# value is an int.

self.value = value

def inc_and_print(self):

self.value += 1

print(str(self.value))Added above in comments are the documented usages of the methods. Particularly, these methods require the argument to be an int.

And now consider the following sequence of calls:

>>> x = Incrementor(4)

>>> x.inc_and_print()

5

>>> x.inc_and_print()

6Looks good so far. Note that the constructor call Incrementor(4) followed the documented usage by passing 4 as the argument, which is an int.

Now consider the following sequence of calls, continuing on from above:

>>> x.change_value("twelve")

>>> x.inc_and_print()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "/home/simshadows/work/tmp/myincrementor.py", line 10, in inc_and_print

self.value += 1

TypeError: must be str, not intThe first statement x.change_value("twelve") was a method call that passed a str instead of an int. Despite deviating from the documentation, the method call succeeded because the operations it performed were supported by the str(since there was nothing more than the value assignment self.value = value).

However, x.change_value("twelve") broke an undocumented invariant that the author of the class definition relied on. In particular, the author of the class relied on self.value being an int.

The next statement x.inc_and_print() then raised an exception because it needed to do something which relied particularly on this invariant.

Indeed, I mentioned duck typing earlier, and it may seem that perhaps this could be solved by instead using a statically typed language such as Java. And indeed, that will help. By having the compiler check on compile time that types are as expected, a great many such errors can be caught at compile time.

However, it’s not a perfect solution because preconditions to functions can go beyond simply type-checking. For example, a function might expect to be passed list with more than 3 elements.

Perhaps I might write another post some day going into more depth on this since this is a rabbithole into software design which goes beyond the intended scope of this blog post.

2017-09-12

So I’ve been thinking a bit more lately on how I want to structure my blog. So far, I’ve been doing far too much long-format almost-stream-of-consciousness writing (with minor editing to rearrange paragraphs) that’s just really difficult to read. Although, as much as I’d like to write a tonne and be precise about everything, perhaps there’s a better way?

Finding and establishing an effective blogging format is also of particular interest since I’m interested in using this as a public learning diary, yet I don’t want to spend too much time writing. I just want to get down and do.

So for a while, I guess my blogging style will shift around while I look for a sweet spot.

And on top of that, I’m also looking into figuring out how the categories should work and how I might organize the whole blog (and the other blogs) to make it easier for people to browse through, especially newcomers.

2017-09-10

So very quickly following my last post here on my initial thoughts with starting Vim, I proceeded to learn tmux first to immediately replacing my habit of constant spawning of new terminals in i3. So far, I’ve found this to be a nice, gentle introduction to the concepts and the commands before I move onto denser reading.

However, I’ve so far found some of the default keybindings to be really horrible to remember. Though one could say I should just rebind everything to suit my needs, I think the issue of whether to keep with defaults or to customize is actually a bit more complicated than it might first seem.

Why does tmux’s vertical splitting have to be C-b + " and horizontal splitting be C-b + %? At least i3 uses $mod-v and $mod-h, which make lots of intuitive sense and meant it took no time at all to get comfortable with them.

Another issue I have is the extremely strange choice for Vim to have the HJKL as the default directional keys, which is something I mentioned in my previous post. Of course, the reason these keys were chosen in the first place was historical, and standards such as this can get so settled that changing them will only cause anger, confusion, and broken software (as I imagine some things such as plugins and scripts can rely on them). I’m not saying we should get everyone together and devise a new standard to change the defaults to (though if needed, making a new widely recognized standard in which people optionally configure to, or even have things officially support might be cool).

i3 however has it right by assigning JKL; as the direction keys, as it should’ve been in the first place (at least in my opinion). This one’s understandable since default $mod-h is used to make a horizontal split container, though it only further complicates things. If I kept HJKL for Vim and everything else, should I just keep i3’s JKL; and remember to right-shift my hand each time? Or should I rebind i3 to maintain parity between all my keybinds? If I rebind, what do I rebind $mod-h and $mod-v to now?

Perhaps I should maybe just save myself the pain and rebind everything. Hell, maybe I should change the direction keys to IJKL (which makes a tonne of intuitive sense, being T-shaped), though that would mean I’d need to rebind Vim’s insert mode key.

I could perhaps get into more, but I think that would be for another blog post (if I choose to discuss this further), or perhaps it might be best if I learn tools first before criticizing their specific choices.

In favour though of rebinding is the reduced complexity of completing many tasks as my brain would have less mental overhead when switching between contexts of controlling Vim, tmux, i3, and whatever other program such as ranger. If I had to switch from Vim’s HJKL to i3’s JKL;, I might first have to consciously reframe my mind to switch keys. In Vim, if I wanted to move in a direction (one step at a time at least), my mind would be automatically translating my intention to unconscious mechanical movement of my fingers to strike HJKL for their respective directions. By switching to i3, I’d have to “reconfigure my mind on-the-fly” to instead translate direction into finger movements that hit the JKL; keys. The solution would clearly be switching everything to use the same direction keys.

Similarly can be said with different pane-splitting in tmux (C-b + " and C-b + %) vs i3 ($mod-v and $mod-h).

Rebinding can also optimize hand movements if done correctly. Sure, I could one day get used to the different controls, but if I optimized my bindings to make the most common operations require the least travel time or contorted hand gestures, the long-term comfort could be worth it.

Some keys can also lack any mnemonic connection. How do C-b + " and C-b + % have anything to do with horizontal and vertical splits? If I end up taking a break from using tmux (such as a long holiday), or during any “brain farts” where I randomly forget my keys for a second, being able to work backwards from mnemonics could make things easier to ease back in.

The first and most important issue I think with whether or not to rebind is that getting used to my own weird keybinds will mean I’ll have a lot of trouble using systems that aren’t mine. If I’m pair-programming, I’d like to know that my partner would be able to use my machine, and likewise I’d like to know that I’d be able to use their machine. Or perhaps if I’m working on a company machine, if for whatever reason I’m stuck with default Vim, I’d like to know that I’m still capable of using it. Or perhaps I’m just quickly connecting to a web server to make a few adjustments, only to find I have to spend a quick minute making some large changes to a config file which would be much easier with Vi. Being able to just jump right into everything with no issue would ultimately make me more efficient and productive.

I’d also be able to use Vim emulators in IDEs and such out of the box.

But what if I could just get used to it? After maybe a year of constant daily use, I’d likely no longer be hindered by these context switches; I’d just do it like it’s second nature. Additionally, if I learnt how to switch contexts like that, I could likely pick up more programs that differ in similar ways much more easily without further being dependent on having to rebind everything to be the exact same. Overall, I’d become a more versatile computer user.

Emphasizing cognitive flexibility might also have an advantage if I choose to pick up a new keyboard layout, such as if I had to work on a German keyboard, or a DVORAK keyboard. With the explicit ability to reframe my mind as needed and rely less on positional motor memory, keyboard layout switches might be easier in the future.

I think I might choose to roll with defaults for the meantime, and only after getting proficient with them will I consider reconfiguring controls.

If I find the controls to be acceptable by then and not inefficient, I think I’ll keep using defaults after that (due to the advantages of everything being readily usable out-of-the-box), but if I choose to remap, at least I’d then have a better understanding of how I use the program to optimize my usage. Only by then will I know my common-cases and other habits.

2017-09-07

So over the past few days, I’ve been thinking of starting off with Vim. I really can’t pinpoint the exact moment or thought process that led me to start down this route, but it continued on to become my current course of action: To force myself to use Vim for all my text editing (or at least within my Linux VM).

Along with that, I’ve also decided to further “Vimmify” my life by using more terminal-based tools (especially if they have Vi keybindings or they synergize well with Vim), using Vim emulator plugins for IDEs and graphical editors, and maybe rebinding keys on various programs to conform to Vi. I’m still in the process of exploring what exactly I can do, but for now, I’ve decided to also use tmux and ranger.

Rather helpfully though, I’ve been using exclusively i3 for the past 2 months, and at this point, I’m actually quite comfortable with it. Not that it took long. There actually isn’t much complexity in the way of being productive with it at a basic level, maybe taking only 5 minutes to learn how to spawn terminals, set orientations, move things around, and use workspaces.

After getting comfortable with Vim, I’m interested in then moving on to Emacs, using Evil. However, that’s an almost completely different rabbithole that I think I’ll head down after achieving my current goal of becoming a Vim user.

That’s my full plan. So what do I expect to get out of it?

Currently, I use Sublime Text as my main editor, usually on my host Windows/OSX system, and using shared folders used within a Linux VM running on Virtualbox. And within Linux, I’ll tend to have many terminal windows open, flick between them in i3, and do any filesystem heavy lifting in a graphical file manager (usually on the host system since I do a lot of work in the shared folder; I don’t remember the last time I opened Thunar since I’m fairly comfortable with a plain terminal). However, since Sublime Text on the host is limited to the shared folders, if I need to edit anything else in the Linux VM, I use nano.

Within Sublime Text, I am a very point-and-click-heavy user, though I still navigate short distances with a flurry of direction-key keypresses. And if I need to delete a large section, I’ll either rapidly hammer backspace (usually if it’s about a word long), hold backspace (usually up to about a long line long), or just use the mouse.

Having seen videos and people move around and edit super-quickly with Vim, and having done a bit of vimtutor on the train (I’m roughly halfway), it’s hard not to be curious as to whether or not I’m capable of achieving the same level of efficiency in text editing, especially considering the very command-based nature of Vim (as opposed to the graphical nature of Sublime Text without plugins). Instead of extremely repetitive keypress spam, awkward hand movements to reach the direction keys, and slow yet imprecise mouse point-and-click action, Vim appears to trade much of that for highly efficient key combinations and hand movements, albeit at the cost of requiring the user to memorize and commit them to muscle memory. Similar can maybe be said with Vim-inspired tools such as ranger.

And in addition to making text editing more efficient, I’m also interested in becoming familiar with more advanced features and extensions, and simply exploring more tools and seeing what fits.